Publications Medical & Scientific Instruments (also found under Surgery)

The Evolution of Surgical Instruments

An Illustrated History from Ancient Times to the Twentieth Century

John Kirkup, MD, FRCS

With A Foreword By James M. Edmonson, PhD

$275.00

The Evolution of Surgical Instruments is the first comprehensive work on the subject published in over sixty years and arguably the most important general history of surgical instruments ever published. The only prior work on the subject, C. J. S. Thompson’s The History and Evolution of Surgical Instruments (1942) attempted to cover the entire history in only 113 pages. Elisabeth Bennion’s Antique Medical Instruments (1979) concentrated chiefly upon the aesthetic aspects of medical and surgical instruments to 1870. James Edmonson’s comprehensive history, American Surgical Instruments (1997), focused on instruments manufactured in the United States up to 1900.

xviii, 510 pp. 579 illus., 30 in color. 8 1/2" × 11". Index. Cloth, dust jacket, acid-free paper. ISBN 0-430405-86-2. Norman Surgery Series No. 13. NP 38632.

- View Complete Index

- View Complete Table of Contents, Preface, and Foreword

- Download a Sample Chapter—Chapter 19: Retractors, Dilators, and Related Inset-Pivoting Instruments

» Skip to: Reviews | About the Author

From the Foreword by James M. Edmonson, Ph.D.

“Perhaps Dr. Kirkup’s most useful and welcome contribution lies in his logical approach to the subject of surgical instrumentation.… He traces eight primary structural forms and their changes and evolution over time.…

“Although instrument form comprised the chief focus of Dr. Kirkup’s work, the development of instrument materials became an equally important interest over the course of this study. As he reveals, the symbiosis between medicine and technology took different forms. On the one hand, advances in technology spawned opportunities for medicine and surgery; new and different materials opened broader vistas to instrument design, as demonstrated by the advent of cast steel in the eighteenth century, hard rubber or ebonite in the mid nineteenth century, and the introduction of stainless-steel alloys around 1912. On the other hand, technical developments outside medicine proper called forth new forms of instrumentation and medical technology in unexpected ways. Advances in weaponry, for example, gave rise to elective amputation and related instrumentation, while industrial accidents promoted the spread of blood transfusion and improved hemostasis. Collectors of surgical instruments and curators of such collections will undoubtedly be interested in Dr. Kirkup’s analysis of the composition of instrument materials over time. This analysis is based upon his thesis in medical history. Rather than rely solely upon impressionistic generalizations, he devised a quantitative means to analyze instrument materials in different eras. He devised a point system and uses it to assess the composition and distribution of materials in collections. This methodology is applied to artifact collections that he has studied in Britain, on the Continent, and in the United States, and also used to analyze instruments appearing in early surgical treatises and in trade catalogues and other ephemeral literature.”

About the Author

John Kirkup M.D., M.A., F.R.C.S., Dip. Hist. Med. studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge and St Mary’s Hospital, London, qualifying in 1952. After service in the Royal Navy he worked as an orthopedic surgeon for the Bath Clinical Area, Somerset, introducing ankle joint replacement to the United Kingdom in 1976.

Always intrigued by the evolution of surgery from its pre-historic roots, Dr. Kirkup edited facsimiles of Wiseman’s Of Wounds (1676) and Woodall’s Surgions Mate (1617), published A Historical Guide to British Orthopaedic Surgery, and contributed chapters in books on Ambroise Paré, on pain management during surgery, on trepanation, on the battle against infection, on damaged surgeon’s equipment of the Mary Rose shipwreck and on instrumentation generally. He published a wide variety of journal communications including an extended series on surgical instruments and on the history of foot and ankle surgery, and twelve surgical entries in the New Dictionary of National Biography. He has been Hunterian, Vicary, Sydenham and Hamilton Russell Lecturers, was awarded the Sir Arthur Keith Medal of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, and has advised widely on museum collections, especially in the UK, Portugal and Australia.

Formerly President of the British Society for Medical History, President of the History Section of the Royal Society of Medicine, Honorary Archivist of the British Orthopaedic Association and Chairman of the Historical Medical Equipment Society, Dr. Kirkup is currently Honorary Curator of the Historical Instrument Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons, London, and Lecturer in Surgical History to the Society of Apothecaries, London. He is completing a book on the historical evolution of limb amputation.

Reviews

“[The book] is magnificent, both in form and function, and will become an invaluable addition to studies in the history of medicine.”

—Ira M. Rutkow, M.D., Dr. P.H.

“Anyone who followed the Rogeon instrument auction in Paris, or has a more general interest in medical history, will grapple happily with this new 500-page survey by John Kirkup, Honorary Curator of the Historic Instrument Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons.

“The book is divided into four sections—Historical Introduction; Materials; Structure & Form; and Applied Instrumentation—and, to give you an idea of the depth of Kirkup’s treatment, individual chapters cover Probes, Needles, Blades, Forceps, Scissors and Clamps.

“Kirkup seems particularly keen on amputation. After reminding us that Sushruta Samhita of ancient India recommended amputation ’as high as the wrist and ankle for infected thorns embedded in the hands and feet,’ he writes with gusto of the army colonel trapped in a crashed helicopter in the Malaysian jungle in 1964, who had his arm amputated without anesthesia using a clasp knife, bayonet, fishing-line and a pair of socks.

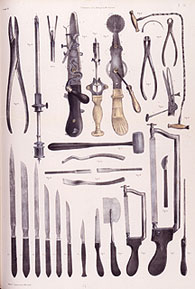

“Kirkup has even tracked down a photograph of the sockless colonel and his army doctor, just one of 548 black and white illustrations (complemented by 30 color plates) featuring not just photographs of instruments and instrument makers, but also Attic vases, Egyptian tombs and medieval woodcuts. The illustrations are placed admirably close to the relevant text.…

“Kirkup loves quotes—’let their jaws be like a bird’s beak’ as Theodoric of Bologna so memorably wrote about forceps in 1267—but his own style can be ponderous.… But the reward for efficiently evacuating the jargon and Proustian sentences is a welter of information, both quirky and technical, laced with Kirkup’s love for his subject and some refreshing value judgments. J. F. Charriere was the ’most imaginative surgical instrument maker of all time,’ while Arbuthnot Lane’s reputation ’ultimately suffered’ because he ’mistakenly believed that chronic constipation necessitated extensive bowel section.’ Ouch.

“Don’t be put off by the gory medieval amputation scene on the cover. This is a beautiful book and, say publishers historyofscience.com of California, the ’first comprehensive work on the subject in over 60 years.’

“It has a 37-page index, a 16-page bibliography, lists 100 museums worldwide exhibiting surgical instruments, and presents a table outlining pivot-spring percentages in forcepts between the 1st century AD and 1963. Kirkup’s vision is encyclopedic, his analysis microscopic.”

—Antiques Trade Gazette (June 17, 2006)

“This well-researched, illustrated history covers the origins of surgical instruments, early concepts of surgery, and technological factors that guided the development of the instruments. Historical sources are looked at, as are the myriad of materials used in making the instruments. The instruments themselves are presented, grouped by form and use, and very closely examined. Not a book for the faint of heart, this is an in-depth and informative look at the evolution of surgical instruments. The author is an orthopedic surgeon as well as a medical historian.”

—Maine Antique Digest (August 2006)

“…A remarkable source of information on a wide range of surgical topics from amputation to vaccination. The credentials of the author are impeccable: Kirkup is an orthopedic surgeon with a lifelong passion for the history of surgery. He was President of the British Society for Medical History and of the History Section of the Royal Society of Medicine, Chairman of the Historical Medical Equipment Society, and currently serves as Honorary Curator of the Historical Instrument Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons, London.

“His approach to the evolution of specific instruments is based on a logical and systematic classification of their structure, composition, and function. It all began with the probing index finger, likely to be the oldest surgical instrument, which was the precursor to the use of a stick or bone to find a foreign body. Kirkup shows how instrument design evolved from the action of fingers, nails, teeth, and mouth into eight fundamental shapes. As advances were made in materials and fabrication to meet the demands of surgical innovation and the requirements of sterilization, instruments changed into forms that we are familiar with today. But this book is more than a chronology of design. As a surgical historian, Kirkup interweaves the story of the evolution of surgical thought and practice, including misguided directions such as intentional bleeding and scarification.

“Throughout, the book is richly illustrated, primarily in black and white, but also with a section of color plates. Some of the scenes are graphic and disturbing, a reminder of what surgeons did and patients tolerated prior to anesthesia. The chapters are heavily referenced, including a bibliographic appendix. There is also a useful appendix that lists museums and collections of surgical instruments by city and country around the world. Since many countries, such as Canada and China, are not mentioned, the list is not likely to be complete, as the author admits. In addition, many smaller collections have less public visibility. But this raises the larger question of how in this country we can preserve the legacy of the tools of our profession as technological changes destine many of them to obscurity in a dusty box. Considering our size and contributions to the field, we do not appear to have made the effort many smaller countries have made to preserve these tangible reminders of our surgical heritage.

“There is little to criticize in such an encyclopedic collection. The author indulges his interest in esoteric areas such as metallurgy to an extent that will exhaust all but the most patient reader. And the classification into eight mechanical categories actually requires an additional one to include mixed and miscellaneous instruments. But much of the detail is unique, such as tables on pivot forceps that list measurements of jaw ratios and handle leverage followed by the calculation of unimanual pressures generated.…

“…Each chapter covers the history of the instrument category up to the present time, identifying the surgeons and technology that made each advance possible. And where else could you learn about ecraseurs, terebellums, or wrenching machines, or the fact that the famous surgeon Jules Pean was painted by Toulouse-Lautrec while operating?

“This beautifully finished book is ideal for perusing between cases or on a rainy afternoon. It would make an excellent gift for a resident or a surgical colleague. It also deserves a place in medical historical collections. The images and stories of our predecessors in connection with the instruments they developed and used serve to remind us that the word surgery means ’handwork,’ no matter how far technology manages to distance us from our patients.”

—Lazar J. Greenfield, MD, in JAMA 296 (August 2006)

Great teachers are able to develop a student’s interest and inspire devotion to it, while the greatest can create that interest where it did not previously exist. I defy any colleague to open this book, browse through its heavily-illustrated pages and not be drawn into reading the text. This is a volume of exceptional beauty and densely packed information. Mr. Kirkup has identified an important aspect of a surgical education and produced a lively, fascinating treatise, the reading of which will generate respect for our surgical forebears and admiration for the heroism of their patients.

The title is well chosen. The author presents evolution rather than history, suggesting an ongoing process based upon pragmatism, and in so doing, presents the evolution of surgery itself. The book is divided into chapters covering prehistory and archaeology, structure and form, materials and applications. The development of the common surgical tools, such as forceps, scissors, probes and clamps is followed meticulously and shows us that they are all continuously changing for functions yet to be defined.

History is not the usual source for surgical instruction, except perhaps to learn what not to do, but this book, a bestiary of operating images, will excite and fascinate. Inevitably the pathology for surgical treatment in ancient times was limited, much being trauma or genito-urinary, but John Kirkup has included all manner of instruments, some for the strangest of procedures. He invites us to look kindly upon the myriad tools for the purpose of shedding blood, and then mercifully, even more for stemming haemorrhage. He covers fully the rivalry between the famous names from the turn of the last century, still attached to artery forceps — Dunhill, Mayo, Kocher, Moynihan, and Spencer Wells who recommended his snap in order “to replace the pinching assistant’s finger and thumb.” The chapter on the tools for closing a wound is a lesson in gentle precision, on how to close a wound, and then again, when and why not to do so.

The application of certain classic pieces of equipment is shown in drawings of their use; for example, the picture of the self-deliverable enema apparatus is a buttock-clenching image. Kirkup has added innumerable comments upon the pictures which would not normally occur to the average voyeur. For example, the reason why amputation of the leg was usually performed with the patient in the upright sitting portion was that he was more likely to lose consciousness and thereby achieve relief.

To study the developing shaped of ancient instruments is to understand the basis for surgical intervention. What leaps off these pages is exactly what the surgeon intended and how it would be performed most expeditiously. Each curve of edge and handle states how force was to be used, or when accuracy and precision were necessary. John Kirkup’s viewpoint is that of a surgeon rather than that of an archaeologist, so his interpretation is patient-oriented. The non-medical reader’s reaction to the artistic depctions of ancient operating theatre drama may generate either horror or laughter; no one will remain unmoved.

It is natural in a book which is so richly illustrated for artistic appreciation to be central to a review. Indeed it would not be possible for the subject to be addressed without pictures, and here they are of exceptional quality. Through them can be seen the basis and background of modern surgery. The decoration of instruments, often in pre-Raphaelite style, carried more than functional importance. In such a scene their embellishment doubtless inspired some measure of confidence. It is interesting that the very last piece of decoration to be stripped, from both instruments and implants, is the name of the manufacturer!

It is clear that this has been one of John Kirkup’s lifelong hobbies. It must have been a difficult decision to known when to stop. He makes no claim that this will be a definitive work, but there is little doubt that it will be a historical treasury, saying as much about surgery in the past few hundred years as many more literary accounts.

Regular readers of these Book Review pages will have noticed a common final sentence of a review to recommend that “although each reader will probably not require a personal copy, such and such a volume should be made available to reference in the hospital library.“ This does not apply to this book. It will be on the treasured shelves in the homes of every surgeon who is both dedicated and devoted to his art.

—M. Laurence, in Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Br] 88-B, no. 11 (November 2006).

…A magnum opus…seems destined to become the authoritative reference work in this area.

—Iain MacIntyre, in Vesalius 12, no. 1 (2006).

…Makes very enjoyable reading for anyone involved in surgery.… The illustrations are plentiful and add greatly to understanding the text.… I would strongly recommend readers to have a look at this work.

—John M. Fitzpatrick, in British Journal of Urology International (Oct. 2006)

The Evolution of Surgical Instruments is a monument. It is the most comprehensive work on this subject ever published and the 20-year gestation period seems trifling in the face of such a detailed and exhaustive tome.…

This book is first and foremost a reference book. It is a vital and unparalleled contribution to the written account of the history of surgery. It will be of interest to a broad audience.… A few will devour it, most will dip in to it and all will be pleased to have access to it in the local medical library.

—John A. Windsor, in Australia - New Zealand Journal of Surgery (April 2007)

There has not been a comprehensive history in English of surgical instruments until now—and perhaps there still has not, for this valuable book might be better described as a historical encyclopedia (or perhaps even a natural history in the eighteenth-century sense) of surgical instruments. John Kirkup has eschewed the temptation of the obvious: this is not a volume devoted to surgical operations that incidentally treats of instruments. Rather, almost completely faithful to the subject, he has built his novel study mainly on two foundations: “Materials,” and “Structure and Form.” A final section, “Applied Instrumentation,” could alternatively be titled “Examples of Use.” A first section, “Historical Introduction and Origins,” contains a most useful chapter on sources for the investigation of instruments, surveying historical studies, surgical works, instrument makers’ and museum catalogues, and more.…

It is in the middle two sections that Kirkup really hits his stride and displays an unrivaled (so far as I know) knowledge of the composition and types of surgical instruments. Chapter 6, misleadingly titled “Organic Materials,” works through animal products (e.g. bristle) and plant matter (e.g. thorns) to stones and minerals. In each case, Kirkup draws on the historical evidence to give examples of the use of these materials; his range encompasses archeological findings and surgical writings from Paul of Aegina to the twentieth century. Chapter 7 continues in the same vein and concentrates on nonferrous metals. Chapter 8 follows suit with ferrous metals, and chapter 9 winds up with “Gum, Rubber and Plastics.” In the section on “Structure and Form,” ten chapters survey types of instruments from probes to retractors, with a score of devices in between; again, Kirkup richly illustrates his text with rare and well-known examples from the historical literature. These two sections will, no doubt, be improved by future additions, but it is hard to imagine any work supplanting them in their entirety.…

—Christopher Lawrence, in Bull. Hist. Med. 81 (2007)

Reviews of Kirkup’s book in German have been published in Minimale Invasive Chirurgie, Vol. 15, no. 3 (2006): 178; and in Sport Orthopädie - Traumatologie, Vol. 22, no. 4 (2006): 261.

« back to all Medical & Scientific Instruments Publications

back to top