Traditions & Culture of Collecting Articles by and about Collectors, Librarians, and Booksellers

Warren R. Howell

Warren R. Howell

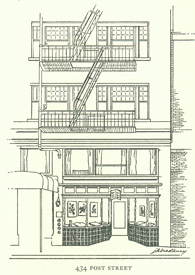

Exterior view of John Howell—Books, at 434 Post Street, San Francisco (from Bohemian Club Library Notes, no. 46 [Spring 1985]).

Exterior view of John Howell—Books, at 434 Post Street, San Francisco (from Bohemian Club Library Notes, no. 46 [Spring 1985]).

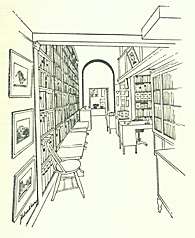

Interior view, looking toward Warren Howell’s office (from Bohemian Club Library Notes, no. 46 [Spring 1985]).

Interior view, looking toward Warren Howell’s office (from Bohemian Club Library Notes, no. 46 [Spring 1985]).

View PDF to read the geneology.

View PDF to read the geneology.Poster designed by Christopher Stinehour, showing the John Howell—Books “family tree.”

Reminiscences of Warren R. Howell Jeremy Norman

originally published in AB Bookman’s Weekly, February 11, 1985; reprinted in Bohemian Club Library Notes, no. 46 [Spring 1985]

About 20 years ago I walked into John Howell—Books in San Francisco to report for duty as assistant to the packing clerk. I was 19 at the time, and I can still remember how awed I was to enter that long, dark, and elegant old wood-paneled store. Built in the 1920s style of Bernard Maybeck, it was filled with books on shelves 10 feet high, with Western American prints and paintings occupying all other available wall space. Over a non-functioning fireplace alcove in the center of the store was carved the motto from Proverbs chosen by Mrs. John Howell: “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

Sitting at the rear of this long, narrow, balconied bibliophilic domain about 100 feet back in a direct line from the front door, framed by the long shelves and the doorway to his private office, was a gray eminence—a handsome, formally dressed, massive hulk of a man, whom I timidly approached. This was Warren R. Howell, then the managing partner (later president) of the firm started by his father, John Howell, in 1912. Next to my father, Warren Howell probably had more influence on the direction of my career than anyone else. During the 20 years in which I knew him he was also a major influence in the international antiquarian book trade, and he informally trained numerous antiquarian booksellers before, during, and after the five and one-half years I worked for him.

A week after Warren Howell died the family held a memorial service in Grace Cathedral, the elegant English Gothic style Episcopal Church on San Francisco’s Nob Hill. Warren was not an Episcopalian. Though he was raised as a Christian Scientist, I never knew him to practice any religion. However it was characteristic of his ability to cultivate many diverse relationships that he numbered among his friends the Dean of Grace Cathedral, who arranged for and officiated at the service. This featured an eloquent and movingly delivered tribute by the historian, novelist, and corporate communications consultant Kevin Starr, who was also former City Librarian of San Francisco. About 900 people attended the memorial service, filling the huge cathedral to capacity. Some friends and colleagues traveled from as far as Chicago, Texas, and New York to attend the service. In the weeks that followed, Warren’s widow, Antoinette, received about 600 letters of condolence from all over the world.

Warren had an exceptionally large collection of friends, many of whom were in high places, and he was not above telling you about them when he was in the mood. If he had any real hobby outside of the antiquarian book business, it was probably socializing. Before his marriage in 1953, he was a founder and president of The Bachelors. Later he officiated as master of ceremonies at the San Francisco Cotillion for many years. He also belonged to the most elite clubs in the city, including the Pacific Union Club and the Bohemian Club.

Warren could be exceptionally charming when he wanted to be and equally supercilious when he did not. He exuded old world manners, tact and politeness. He was proud to point out that he was related to John Ruskin on his mother’s side, and that his great-great-great grandfather at the age of 70 fought alongside his son in the American Revolution. Most of Warren’s customers were equally proud to call themselves his friends.

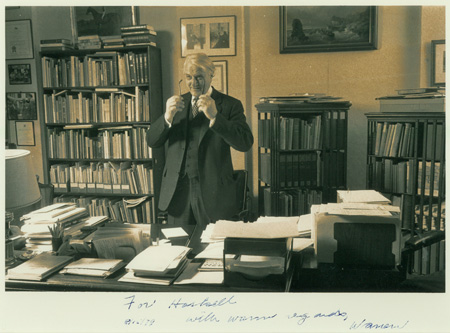

A formal dresser, Warren nearly always wore dark suits and white shirts at the office, except on Saturday when he would invariably wear a sport jacket or blazer. He wore black-rimmed half glasses which gave him an even more aristocratic look, and I still remember how he peered down at me on that day when I first reported for work.

My immediate superior, the head packing clerk, was an artist in the packing room. All of his packages were handcrafted to perfection, and I cannot recall ever hearing that any books were damaged in transit during the years I remained at John Howell—Books. Learning how to wrap books correctly was invaluable experience. It is an essential skill for any antiquarian bookseller, and it is surprising how few expert dealers are really expert packers. I have never forgotten the special knots for tying up packages which I learned at Howell’s, and although we have since developed more efficient and speedier ways to wrap books for shipment, the experience I gained in Howell’s packing room enabled me to train six different packers.

Soon I graduated from wrapping books to running errands and dusting books on the shelves. Perching up on a tall ladder, removing books from shelves so that the shelf could be brushed off with an old-fashioned feather duster, I had the opportunity, over a period of months, to look at virtually every one of the tens of thousands of books in the shop. Any latent acrophobia I might have experienced was rapidly cured. I learned the arrangement of the shop by subject, to the extent that there was an arrangement. I poked through all the little nooks and crannies of this old-fashioned store, generally found out what books were kept where, and I made it my habit not only to dust the tops of the books, but to look inside the covers, to check out the book itself, and the price.

Like his father, John Howell, Warren had the habit of penciling his selling price above his cost code in the upper left corner of the rear pastedown of each book, and in the first volume of a set. Warren’s rationale for placing the price in what I consider an inconvenient location for the customer was based on the rather grand notion that “the price should always be the final consideration.” This grand approach to doing business also allowed Warren to encourage my spending days on end studying all of the books in the store when I could have completed the dusting in a few days. Warren always kept a staff larger than necessary, and my “dusting” kept me occupied when there was little else for me to do.

When it was time for me to come down off my dusting perch to greet the public, I had a pretty fair notion of where things were in the store, and what we were likely to have for sale as well as what we would not stock. Even 20 years ago Howell’s was one of the last general antiquarian bookshops which attempted to maintain a stock of rare books of the finest quality on almost all subjects from art to zoology. In virtually no other store could I have seen, handled, and sold so many important books in such a wide range of subjects. In addition to rare and expensive books the shop also stocked a fair number of high quality out of print books, and a certain residue of old dust-collectors of questionable merit.

Numerically, the largest percentage of inventory concerned California, Western Americana, Hawaii and the Pacific. After that was English and American literature, rare bibles (the specialty of John Howell), sporting books, natural history, maps and atlases, early printing, and a large selection of San Francisco fine printing by the Grabhorns, John Henry Nash, and Lawton Kennedy. Warren also liked to keep a few representative examples of Kelmscott, Doves, and Ashendene in stock, and I still remember selling a few Kelmscotts from the library of T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, hidden away in one of Howell’s closets, to an architect who casually walked in off the street one day. Those were the first purchases of a collector who went on to build the world’s finest private collection of William Morris.

Warren himself was a patron of San Francisco fine printing through the publication of 34 limited editions of Western Americana, mostly printed by Lawton Kennedy. Among the most important of these were the third, revised edition of William Heath Davis’ Seventy-five years in California (1967; first published 1889, second edition published by John Howell, 1929); van Nostrand, The first hundred years of painting in California 1775-1875 (1980); and Galvin, The etchings of Edward Borein (1971). Warren also published the classic Bibliography of the Grabhorn Press 1957-1966 & Grabhorn-Hoyem 1966-1973 (1976). His fourth edition of Wagner & Camp, The plains & the rockies, revised, enlarged and edited by Robert H. Becker (1982), represents perhaps the final evolution of the standard reference work initially published in 1920 by John Howell. This thick 745pp. quarto, handsomely printed by the Arion Press, may turn out to be one of the last large reference works printed by letterpress in the United States.

Initially to satisfy the appetites of Herbert M. Evans (1882-1971), discoverer of vitamin E and the growth hormone of the anterior pituitary, Warren developed a trade in classics of medicine and science. Once retired from academic work, Evans became a collector/dealer, building a series of important collections of scientific and medical classics which Warren and Jake Zeitlin would then sell for him on commission. Because of my special interest in this field, I was always fascinated to sit in on the conversations during Evans’ frequent visits to the store. A polished and exceptionally well-educated gentleman of the old school, Evans had a great reputation as a ladies’ man. He also had the habit of quoting poetry, and he enjoyed a flair for the dramatic which he would sometimes express through the most exaggerated flattery. You can imagine how I felt when, during my first awkward year as a Howell clerk, Evans greeted me by bellowing at the top of his lungs: “Well, if it isn’t my friend, the world’s greatest bookseller!” On a later occasion a more serious Evans shed tears in my presence when he reminisced about his boyhood experiences with his father, a horse and buggy doctor, 80 years before.

Warren also maintained a big stock of gift books such as Limited Editions Club near the front of the store, along with fine sets of standard authors, and deluxe limited edition art books. Other than pornography, there was really only one subject which Howell’s would never stock: genealogy. If you wanted to get Warren wound up you could ask him why he would not sell books on this subject.

With a store like Howell’s you never knew who might walk in off the street. There was the occasional celebrity like Red Skelton, who was a serious collector of both books and oriental art. There was also the occasional panhandler or colorful crazy who had to be led out the door, and there were plenty of interior decorators looking to buy 20 shelf feet of leatherbound books on any subject if the color would fit in with their decor. Only once did such a customer refuse to buy the most gorgeous full maroon morocco, gilt, slipcased set of the complete writings of Gabriele D’Annunzio printed on Japan vellum. The color was just right, but the text was in Italian—one of the many languages which he did not read. I never did fully accept his refusal!

Other customers might be experts on some specialized subject like costume design or the history of the theatre. I found that they were frequently willing to give me a free lecture on their subject if I asked a pertinent question. Thus I learned at this early date that customers will often educate you on their subject, and help you sell to them if you encourage them. But you must know enough to ask the right questions and carry on the conversation. This is one of the fundamental rules of selling.

Whenever one of the customers to whom I was selling turned out to be a serious buyer of expensive books, manuscripts, or art, Warren would usually take this customer for himself, but he would let me observe how he handled the client and would frequently make me a party to the conversation. Of all the antiquarian booksellers I have ever met, Warren was the consummate salesman. Having worked for his father since his teens, Warren, then in his 50s, had vast experience in handling rare books in all fields. He never pretended to be a scholar or a linguist, and he didn’t particularly like to write anything longer than a business letter, but he was relatively well-read and highly intelligent, and he knew whom to consult when he got into an area requiring special expertise.

Like most of the best booksellers, Warren had a superb memory for bibliographic details and prices. What was more unusual about him was that he could apply his memory to social skills. Over and over I saw him remember the names and former purchases of clients with whom he had been out of contact for years. In other instances Warren was the most accomplished name-dropper. This particular skill, developed through Warren’s exceptional social connections, did not have a positive effect on all clients. Warren also had exceptional patience with the eccentricity of collectors, especially wealthy ones. This, combined with his great personal charm, his authoritarian manner, and his wonderful taste in books, frequently enabled him to do business with the rich and powerful.

Fairness, courtesy, and integrity characterized Warren’s dealing with his clients and colleagues. Over 20 years I never knew him to lie, although his sense of tact would occasionally prevent him from speaking an unwanted truth. Early on he told me that the rare book world is so small that any lie told in San Francisco will soon be found out in London, New York, or Paris. Warren’s integrity was of the greatest importance in causing me to choose the antiquarian book trade for my own career. It was inspirational to learn that one could conduct a successful business without recourse to unethical behavior.

In his buying as well as his selling Warren always placed the strongest premium upon condition. Over and over he emphasized the importance of handling the finest available copies of books, and he was always willing to pay the premium for the finest, whether buying privately or at auction. He also felt strongly that it was the role of the antiquarian bookseller to educate his clients about the importance of condition and other rules of serious book collecting.

Warren was especially proud of his Navy record in the Pacific during World War II, for which he was awarded the Navy Bronze Star with Combat Cluster. Over the years Warren received much recognition for his achievements in the book trade, and much acknowledgement for his support of academic libraries. He was the subject of numerous newspaper and magazine articles. He was elected a fellow of the Pierpont Morgan Library, the California Historical Society, and the Gleeson Library at the University of San Francisco. He was also made an Honorary Member of the Society of California Pioneers. He served as president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, and he served on the councils of various important libraries including the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1982 Stanford University Libraries honored him by establishing the Warren R. Howell Award for Book Collecting. The Howell archives are now at Stanford.

John Howell—Books was a San Francisco institution from 1912 until its demise in 1985, and the training ground for numerous successful antiquarian booksellers. These included the late David Magee, John Swingle of Alta California Bookstore, Ronald R. Randall, Jeffrey Thomas, Hans Kraus, Jr., and Barbara Grigor-Taylor of Piccadilly Rare Books, as well as myself. They all have their own reminiscences of working for Warren and their own particular reasons for leaving his employ to start their own businesses. Among the numerous other former Howell employees who continue to work in the rare book and library field are Margaret Tyler (Maggs Bros.), Joan Crane (University of Virginia), and Riva Castleman (Museum of Modern Art).

Warren had two great loves in his life: his wife, Antoinette, and John Howell—Books. He was a classic workaholic who spent 10 to 12 hour days at the office six days a week. These long hours were no doubt a factor in making him one of the most successful antiquarian booksellers in the world, and he continued to maintain them in spite of years of deteriorating health.

With characteristic courage Warren worked in the shop until the end, taking time out only for the increasingly necessary medical treatment. With great enthusiasm he traveled to London to attend the sale of The Gospels of Henry the Lion but was unwell after he returned. During his last days Warren continued to work at the shop until he called an ambulance to take himself to the hospital. There he suffered a series of fatal heart attacks.

Warren faced the end with courage and with boldness. That he touched many lives was demonstrated by the vast number of people who came to pay him tribute at Grace Cathedral. I will always remember Kevin Starr, resplendent in his doctoral robes, his powerful voice reverberating throughout the Gothic vaults, saying, “Warren Richardson Howell was, above all else, a man of deep personal warmth and passionate intensity. In an era of indifference masquerading as sophistication, of cynicism masquerading as wisdom, Warren Richardson Howell was not afraid to care and to care deeply… .”

« back to all Articles

back to top