Traditions & Culture of Collecting Articles by and about Collectors, Librarians, and Booksellers

Haskell F. Norman, age 75

Haskell F. Norman, age 75

Haskell F. Norman, age 30

Haskell F. Norman, age 30

Dr. Norman’s bookplate, designed by Reynolds Stone

Dr. Norman’s bookplate, designed by Reynolds Stone

My Education as a Bibliophile Haskell F. Norman, M.D.

Originally published as an introduction to The Haskell F. Norman Library of Science & Medicine (1991)

As I reflect over my forty years of collecting and the thousands of books that it was my pleasure to acquire, two particular books stand out beyond their significance in the history of science. Both acquisitions were especially influential upon my development as a collector—one began my library of classics in the history of psychiatry, and the other inspired me to collect classics in the history of science and medicine on a wider scale. The first was Freud’s Die Traumdeutung (1900), which announced epochal discoveries about the mind of man, and the second was Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (1543), which revolutionized the study of human anatomy. They came my way about ten years apart.

In 1953, as a psychiatrist undergoing psychoanalytic training at the San Francisco Psychoanalyic Institute, I purchased the first edition of Freud’s Die Traumdeutung for $75. This masterwork on the interpretation of dreams was the book that Freud regarded as his greatest achievement, and it is generally acknowledged to have revolutionized Western thought.1I. Bernard Cohen, in Revolutions in Science (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985) has suggested that Die Traumdeutung was the last great revolutionary work presented to the world in book form rather than in a journal or a monograph series (p. 356). Purchase of this first edition was an important event for me because I did not intend to use the volume for study; it was a collector’s item, a tribute to the master.2The edition I was studying at the time was the new, improved English translation first published in 1953 in the Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, edited by James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1953-1974). In 1952 the text had been also included as Vol. 54 in the series Great Books of the Western World, edited by Mortimer J. Adler. Five years after my purchase, the first edition of Die Traumdeutung would be displayed in the Grolier Club exhibition of One Hundred Books Famous in Science (1958), and five years after that it would be included in the 1963 London exhibition, Printing and the Mind of Man. But before these exhibitions, and their even more influential catalogues, the first edition of Freud’s masterwork was little known to collectors outside the fields of psychology and psychiatry, and even though only 600 copies of the first edition had been printed, I had no trouble obtaining a copy.

As all collectors know, one book is only the beginning. I soon decided to find companions for Die Traumdeutung, and added first editions of Freud’s other books as well as those of his colleagues and precursors. Since I was teaching the history of psychoanalysis and psychiatry from classical antiquity to the present, it was easy for me to rationalize extending the collection to first editions ranging from Greek philosophy (Plato, no. 1714; Aristotle, no. 70) Roman medicine (Celsus, no. 424), the Middle Ages (Michael Scot, no. 1507), the beginnings of modern psychiatry in the sixteenth century (Weyer, no. 2209) to the humanitarian reformers of the late eighteenth century (Chiarugi, no. 475; Pinel, no. 1701 and Tuke, no. 2109), and finally to the development of psychotherapy (Mesmer, no. M4; Braid, no. 324; Liébeault, no. 1347; Bernheim, no. 210; Charcot, nos. 445 and 451). During my first decade of collecting, my acquisitions on the history of psychiatry, as I chose to define that subject, were made mainly from dealers’ catalogues and through correspondence. I was not yet a member of book clubs, rarely visited bookshops, and knew very few other bibliophiles. Luckily I did establish contact with a number of rare book dealers who specialized in the history of science and medicine.

The most prominent of these dealers at the time was Dr. Ernst Weil, formerly of Munich, and then in London, who was widely recognized as the most distinguished authority in the fields of science and medicine. I had read his article, “A doctor and his books: The formation of the Harvey Cushing collection”3Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences I (1946), pp. 234-246. and this prompted me to write him to acquaint him with my interests. I soon received some of his catalogues from which I ordered a number of good things. In retrospect I realize that my fields of collecting—psychoanalysis and psychiatry—were not especially popular with other science and medicine collectors at the time because I usually was able to obtain what I ordered from most dealers’ catalogues.

At any rate Weil soon began to send me special offers. One important item was the offprint of Freud’s Über Coca (no. F7) inscribed to Prof. A. Vogl, whose library Freud had used in preparation of the article. This unique presentation impressed me so much that I began to favor presentation copies thereafter. Weil also encouraged my purchase of the de Thou copy of the fifth edition of Weyer’s De praestigiis daemonum (no. 2212), despite the fact that I had earlier purchased from him a fine copy of the same edition bound in contemporary vellum. This was his way of introducing me to books in notable historic bindings, volumes which have always been especially rare in science and medicine. Not too long ago I was fascinated to read that ten years after Weyer’s death in 1588, de Thou, then President of the Parliament of Paris, was responsible for sparing the life of a psychotic man who had been sentenced to death as a witch; instead, de Thou had the man committed to a hospital. Perhaps reading this very copy of Weyer’s book influenced de Thou’s decision.

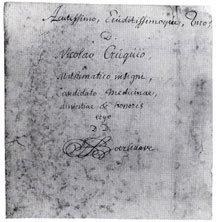

I am grateful to Weil for another famous psychiatric rarity, Chiarugi’s Della pazzia (no. 475). Chiarugi was the first physician to introduce humane reforms in the treatment of the mentally ill, preceding Pinel in France. Chiarugi’s book is so rare that I have heard of only two other sets changing hands in almost forty years. Legend has it that most copies were lost in a flood of the river Arno.

In 1959 on a visit to London I met Weil for the first time and was delighted with the experience. Having corresponded with him almost weekly for several years it was as though we were old friends. Weil conducted his business from home, as many others did, and first received me graciously for afternoon tea. Later, after reviewing my collecting interests, he showed me some of the treasures he intended for his next catalogue, Renaissance medicine, no. 30. It was either during this visit or perhaps later that he showed me two books that I now regret passing up—Johannes Peyligk’s Compendiosa capitis phisici declaratio (1513) and Eucharius Rösslin’s Der swangern Frawen und Hebammen Roszgarten (1513). Neither of these books is in my library today. They were the sort of book that previous customers of Weil—Harvey Cushing or Erik Waller—would have risen to.

I believe it was during this same visit that I met at Weil’s home Richard Hunter and Ida Macalpine, the mother and son team of psychiatrists, who were assembling the great library of English psychiatry that became the source of their book, Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry, 1535-1860 (1963). Meeting them enabled me to understand why more recently I had been less successful in obtaining some of the psychiatric books I ordered from European catalogues. They were my competition and being in Europe they usually pre-empted me.

On this trip to England my wife, Rae, and I were accompanied by our two children, Jeremy and Carol. Weil graciously invited Jeremy, then fourteen years old, and me to accompany him to a book auction at Sotheby’s—one of the Earl of Bute sales, I think. This was my first auction experience and I was impressed with the books and the prices. Weil made only a single purchase, a rather mediocre copy of the first Greek Euclid which he subsequently had washed and bound in red morocco by Sangorski & Sutcliffe. I must already have been tempted to collect the great books in science and medicine because I decided to purchase the book as a souvenir of our trip, also hoping to interest my son in the great books. Some years later I replaced this copy with a much more desirable one purchased from Otto Ranschburg of Lathrop C. Harper in New York (no. 730).

Another bookseller who provided me with some choice books during those early years was F. Thomas Heller of New York. He was a Viennese expatriate, the son of Hugo Heller, one of Freud’s early colleagues and later Freud’s publisher. I learned to my regret that Heller’s parents had divorced when he was very young and that he had little recollection of his father and possessed nothing that linked his father to Freud. It was Heller who sold me Mathilde Breuer’s copy of Breuer and Freud’s Stüdien über Hysterie (no. F27) as well as Freud’s Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse (no. F92) inscribed to Oskar Pfister, a Protestant minister and practicing psychoanalyst. Until very recently this was the only one of Freud’s publications in my collection that had been presented to a practicing psychoanalyst. Much later Heller also sold me copies of three of Freud’s earliest biological papers, which he had presented to his friend, the chemist Josef Herzig (nos. F3, F5 and F6). Other important purchases from Heller were the first edition of Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft (no. 1915), Nicolas Bergasse’s Théorie du monde (no. M50) and the presentation copy of Jean Pecquet’s Experimenta nova anatomica (no. 1676).

During the 1960s I was in active correspondence with many British booksellers and made it a regular policy to visit them whenever I traveled to London. On my annual trips to Europe I seldom failed to see Richard Gurney; Herbert Marley and later John Boyle of Dawsons of Pall Mall; Hugh K. Elliot; E. H. Boxall and later William Watson of Bernard Quaritch, Ltd.; Francis Edwards, Ltd.; Brian Maggs of Maggs Bros.; H. K. Swann of Wheldon & Wesley, and others. A number of these men ran their own one-man businesses, and when they died, their businesses dissolved. This was the case with Weil and Elliot. Richard Gurney, from whom I purchased more books than any other English bookseller, recently ended his business by retiring.

I had been collecting actively for six years before I finally visited the leading bookseller in San Francisco, Warren R. Howell of John Howell—Books. Howell was to become another major influence in my bibliophilic career. My first purchase from Howell was a copy of the editio princeps of Sophocles, the Aldine octavo of 1502 (no. 1976), which contains the first edition of Oedipus rex, an obvious book for a psychoanalyst. Today I recall with some embarrassment that Warren offered me a choice of two copies—one in a contemporary Venetian binding and another rebound copy at half the price. Unwisely I purchased the latter.

It soon became my routine to visit Warren Howell on Saturday afternoons. After many years of hardship he was on the verge of achieving prominence in the national and international book trade. In the past he had been known as a specialist in bibles, Western Americana, English and American literature, travels, and fine press books. Now he was beginning to deal in science and medicine. He enjoyed sharing his wide general knowledge of books and displaying his treasures. Warren stressed the importance of owning books in fine condition, and to him I owe most of my appreciation for condition as a most important selection criterion in book collecting. Among the many books that I acquired from Warren over the years were the Gutenberg Bible leaf (no. 229); Dondi’s Aggregator (no. 649) in a fine contemporary binding; Bagellardo’s De egritudinibus & remediis infantium (no. 102); the editio princeps in Greek of Plato’s Opera omnia from the library of Michael Wodhull (no. 1714); Copernicus’s De revolutionibus (no. 516); the first English translation of Thomas Geminus’s Compendiosa totius anatomie delineatio (no. 887), perhaps the only complete copy in private hands; Bartolomeo Eustachi’s Opuscula anatomica (no. 739); and Esquirol’s interleaved and heavily annotated copy of his psychiatric classic, Des maladies mentales (no. 724). With Warren, too, there were several great books that I failed to acquire, including the privately printed first edition of Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598), the offprint of Luigi Galvani’s “De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius” (1791), and the first edition of William Harvey’s De motu cordis (1628). However, like many collectors, I was often stretching my financial resources, and in these instances my decision not to purchase was usually based on financial considerations.

In 1961 Dr. Bernard Diamond, a bibliophile colleague in San Francisco who had assembled a fine library emphasizing psychoanalysis, psychiatry and especially forensic psychiatry, invited me to meet Herbert M. Evans. He informed me that Evans had asked to see his psychiatric books. In years past I had heard of Evans as an almost legendary biologist, renowned for several great discoveries including Vitamin E and the growth hormone of the anterior pituitary. Until that evening I had had no idea that Evans was a bibliophile as well. Although Evans was then seventy-nine he was still a very impressive, tall, handsome, and eloquent man. It seemed that Evans at this time had decided that the great books in psychiatry deserved his attention. He acknowledged that he was a collector of science and medicine. I was quite awestricken when he later requested to see my collection as well. During our second meeting at my home I presented him with my duplicate copy of the 1577 edition of Johann Weyer’s De praestigiis daemonum, and he reciprocated with inscribed copies of his monographs on Vitamin E (no. 742) and the chromosomes in man (no. 744).

These two meetings with Evans had a profound impact on me. Not long afterwards, Warren Howell offered for sale Evans’s collection of several hundred first editions of books important in the history of science and medicine. I looked at his books with more than passing interest but could not bring myself to purchase them although I could have easily managed the $85,000 for which the collection eventually sold. The thought of possessing the collection which this aged great man was forced to sell in his decline was unappealing. In retrospect it was a great bargain; it is now the nucleus of the Barchas collection at Stanford University. Today the copy of the first edition of Huygens’s Horologium oscillatorium (1673) bound in contemporary full red morocco and presented by the author to Isaac Newton, would be worth more than the cost of the whole collection. You may readily imagine how ridiculous I felt when I discovered that this was Evans’s fifth science collection, and that he had already built and sold four earlier ones.

Evans was in fact the pioneer collector of books in the history of science. Collection No. 1, “Classics in the medical sciences,”4The titles for Evans’s collections are taken from Jacob I. Zeitlin’s “Herbert M. Evans, pioneer collector of books in the history of science,” Isis 62 (1971), pp. 507-509. was sold as early as 1930, and was the property of the Denver Medical Society until 1975, when it was dispersed, by order of the trustees of the Society, at Swann Galleries (sale no. 984). Many of the books subsequently found their way to Japan. Collection No. 2, “First editions in the sciences, together with a reference collection on the history and bibliography of science,” was purchased by Lessing J. Rosenwald in 1950, and presented by him to the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton. It was sold on behalf of the estate of Evans’s first wife by Zeitlin & Ver Brugge and John Howell—Books. Collection No. 3, also titled “First editions in the sciences, together with a reference library on the history and bibliography of science,” was purchased in 1953 by Zeitlin & Ver Brugge and sold by catalogue. Many of the books were acquired by Bern Dibner for the Burndy Library (now the Dibner Library, Smithsonian Institution) and the E. L. De Golyer Collection (Oklahoma). Collection No. 4, “First editions in the sciences,” was purchased in 1957 by Bernard M. Rosenthal and John F. Fleming for Louis Silver of Chicago. Collection No. 5, another “First editions in the sciences” (1961) was sold by John Howell—Books and Zeitlin & Ver Brugge to Samuel Barchas, as mentioned above. Collection No. 6, “First editions in the sciences, together with a collection on the history and bibliography of science,” was apparently hastily assembled. In 1962 it was sold by John Howell—Books and Zeitlin & Ver Brugge to Lew D. Feldman of the House of El Dieff. It is now at the University of Texas at Austin. Collection No. 7, “First editions in the history of science and a collection on the history and bibliography of science,” was purchased by John Howell—Books and Zeitlin & Ver Brugge and dispersed in their catalogues. The major part is at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Jacob Zeitlin estimated that during his lifetime Evans had assembled (and sold) at least 20,000 volumes. In addition to the science collections Evans made at least two great collections of Western Americana, two collections of Japanese prints, one collection of the prints of Jacques Callot, and one library of important books of poetry, art and the humanities.

After the sale of Collection No. 5 I would frequently meet Evans on my Saturday afternoon visits to John Howell—Books. Evans came to examine the books that Warren Howell had purchased for him either at auction or from other dealers. By this time it seemed that Evans was regarded as a very slow payer by most booksellers. To quote Jake Zeitlin, Evans’s “appetite for books often outran his purse.” This explained Evans’s need to sell his collections and start again—occasionally even repurchasing some of the books he had previously sold.

As a bibliophile Evans had a great deal of knowledge and exquisite taste. He had studied medicine at Johns Hopkins, and recalled that he had been inspired to study the history of medicine after hearing Sir William Osler lecture there on Michael Servetus in 1906. Thus there had been a direct link between Evans and Osler. Evans had also worked with Harvey Cushing while at Hopkins, and it is through Evans that I relate myself to both Osler and Cushing.

Of limited means, Evans was unable to begin collecting until he was established as a professor in 1915, and was able to obtain access to some funds his wife had inherited. However, Howell informed me that Evans had told him that he (Evans) had purchased the first edition of Aselli’s De lactibus (1629) as early as 1912. I still recall vividly Evans’s exuberance when Warren brought forth an occasional rarity that Evans was capturing for his next collection. One of these was a pristine copy of Pasteur’s thesis (1847); another was a mint copy of Sadi Carnot’s Réflections sur la puissance motrice du feu (1824) in the original wrappers; a third was a fine copy of Vesalius’s Fabrica (1543) in contemporary blind-stamped pigskin. It was an education to hear Evans and Howell discuss the relative merits of copies in their original state, in contemporary bindings, etc. The choice of the copies of many books in my library was undoubtedly influenced by these discussions. Until that time the most expensive book I owned was the first edition of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1620) which I had purchased from Bernard Quaritch, Ltd. in contemporary blind-stamped calf for about $2,000 (no. 381). It must have been my chagrin at not purchasing Evans Collection No. 5, as well as the thought of this “old man” seemingly spending several thousand dollars more each week, that challenged me to emulate him. I decided to broaden the scope of my collection to include the great books in science and medicine.

On a visit to London in 1962 I told Weil that I wanted to possess one great science book and asked him to propose it. This did not take Weil very long. He informed me of the availability of a copy of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus (1543) inscribed to one Andreas Goldschmidt on 20 April 1543 by Rheticus, Copernicus’s disciple, who was responsible for the book’s publication. It was a beautiful copy in contemporary blind-stamped pigskin. The date of Rheticus’s inscription belied the legend that De revolutionibus had been placed in Copernicus’s hands on his death-bed, as the inscription was dated three months before Copernicus’s death. Weil said the book had been in the hands of another bookseller for about a year and that he thought I might have it for $12,000. I asked him to purchase it for me.

Returning to San Francisco, I mentioned the proposed purchase of the Copernicus to Warren Howell and Herbert Evans on my next Saturday visit to John Howell—Books. Evans promptly informed me that the book had already been purchased by Harrison Horblit of New York. Since I had just narrowly missed purchasing the book I decided I wanted at least to see it. Accordingly at my request Evans wrote a letter of introduction to Horblit so that I might visit him on my next trip to New York. It was thanks to Evans that Horblit invited me to his home to see his great collection of science books. And what a thrill it was! Horblit had begun to collect books in the late 1940s or early 1950s, beginning first with the history of navigation, and eventually widening his scope to cover the history of science in general. He had been a great customer of John F. Fleming, successor to the Rosenbachs, and many of the fine early books on navigation in his library had come from the residue of the Rosenbach inventory acquired by Fleming. Out of this business relationship Horblit and Fleming had built a very close personal friendship.

Horblit had superb taste. In addition to the Copernicus he showed me almost too many great books to enumerate. Perhaps the most fabulous was the Ulm Ptolemy printed on vellum and completely hand-colored. Other books I remember were the first Pliny (1469) and a superb Kepler Astronomia nova (1609). Harrison was a generous host and I had the pleasure of visiting him in New York annually until he retired to a mansion in Ridgefield, Connecticut. Each visit contributed further to my education as a bibliophile. On one New York visit Horblit introduced me to the aforementioned John Fleming, whose baronial New York offices had been created for Dr. Rosenbach.5See no. 860 in this catalogue for Sesto Prete’s Galileo’s Letter about the Libration of the Moon, which was presented to me by Horblit and Fleming at the time of my visit to Fleming’s office. It is regrettable that Horblit’s superb library never was adequately catalogued. For undisclosed reasons Horblit discontinued the auction of his books at Sotheby’s (London) after the second sale, completing only the letters A through G (1974-1975).6Sotheby & Co. The celebrated Library of Harrison D. Horblit Esq. Parts. 1 & 2. Early Science, Navigation & Travel, with a Few Medical Books. London: Sotheby & Co., 1974-75. The remainder of his magnificent library was eventually acquired by H. P. Kraus, who offered many of the books in various of his bookseller’s catalogues.

Another notable collector I met was Robert B. Honeyman IV, who kept his very large history of science collection in a separate building specially constructed for the purpose at his beautiful home in San Juan Capistrano, California. Honeyman’s library evolved from an interest in early mathematics, and included almost every edition of Euclid, several mathematical incunabula and some superb medieval scientific manuscripts. Warren Howell arranged for Jeremy and me to visit Honeyman’s home for lunch one Saturday. Mr. Honeyman received us in his library where I was surprised to see literally thousands of books of various sizes and shapes all shelved in identical bright red half-morocco slipcases—one can only conclude that Honeyman was particularly fond of red. Also displayed in their home was Mrs. Honeyman’s fine collection of impressionist paintings, a collection far smaller in number, but probably more valuable in monetary terms, than Honeyman’s remarkable library.

It was Honeyman who purchased the extremely rare Galvani offprint (1791) that I had earlier passed up. Another book that I will never forget was Honeyman’s fine paper copy of the 1628 Harvey. As a collector Honeyman did have one notable peculiarity—he would never spend more than $4,000 on any one book or on any single day, and if books he wished to purchase happened to exceed this amount he would offer Howell or Zeitlin other books in trade to make up the difference.

An early customer of Henry Zeitlinger at Sotheran’s, Honeyman had begun collecting as early as the 1920s. For a time he was a major benefactor of the library at Lehigh University, to which he contributed some remarkable books, including the original hand-corrected galley-proofs of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), a treasure that had been sold to him in the 1950s by Warren Howell. For estate planning purposes Honeyman eventually wanted to sell his library, and Jake Zeitlin took the unusual course of selling it to Sotheby’s. It was dispersed and recorded in the series of seven auction sales from 1978-1981.7Sotheby Parke Bernet & Co. The Honeyman Collection of Scientific Books and Manuscripts. Parts 1-7. London: Sotheby…, 1978-81.

Returning to the history of my own acquisitions, I conveyed my disappointment to Weil at losing the Rheticus copy of Copernicus and Weil responded that if I were patient he would find me another great book. In the interim I asked him to send me a list of what he regarded as possibilities so that I, too, might be on the alert. In 1963 Weil advised me that he had found my “great book.” It was a colored copy of the first edition of Vesalius’s Fabrica (no. 2137). When I related this news to Warren Howell he cautioned me against purchasing the copy. In Howell’s experience most woodcut books, if colored, were usually colored so crudely that they had much less merit and value than a fine uncolored copy. So cautioned I referred the matter back to Weil who soon responded that this book was exceptional in that it had been colored by a miniaturist and illuminated in silver and gold. As a favor he agreed to reserve it for me in Paris where I could see it a few weeks later. The book was at Librairie Thomas-Scheler, and was owned in partnership by Lucien Scheler and Georges Heilbrun, and also, I believe, by Weil.

Prior to my departure for Paris I had carefully reread Cushing’s Bio-bibliography of Andreas Vesalius (1943). This prepared me for the most exciting moment in my bibliophilic experience, for after only a brief glance at the book I was convinced that I held in my hands the long-lost dedication copy of the Fabrica. I had read that Vesalius had delivered a copy of his book to the Emperor Charles V, and this copy, bound in imperial purple velvet, hand-illuminated, and with its inscription from Charles V to the French ambassador, seemed appropriate for an emperor’s library. Cushing had stated initially that the dedication copy was printed on vellum, and that he had seen a vellum copy of the Fabrica in the library of the University of Louvain prior to that library’s destruction by bombing during World War I. However, Cushing subsequently corrected himself and concluded that he had seen instead a copy of the Epitome on vellum. Today there are three extant copies of the Epitome on vellum—in the British Library, the Hunterian Collection at the University of Glasgow Library, and the library of the Escorial in Spain, which possesses the dedication copy to Philip II, Charles V’s son. No copy of the Fabrica printed on vellum has ever been reliably documented.8The earliest reference to this apparent ghost is in von Praet, Catalogue de livres imprimés sur vélin…pour servir de suite au catalogue…de la Bibliothèque du Roi, I (1824), p. 278. Brunet, who also repeats this legend, may have derived his misinformation from that source.

This purchase notwithstanding, when it came to Weil’s catalogues I discovered that I was still not one of his most preferred clients. It was not until the publication of his last catalogue in 1965 that I achieved the status of receiving the very first catalogue before other customers. From this catalogue I ordered several wonderful items only to find that I would not receive any of them—Dr. Weil had died two days after the catalogue was issued.

Purchase of the Vesalius placed me in contact with two great Parisian booksellers, Lucien Scheler and Georges Heilbrun, who were to add significantly to my library, especially during the 1960s. A renowned poet and much-published scholar as well as a bookseller, Lucien Scheler was a longtime colleague of Weil and like him specialized in science and medicine. He was an acknowledged authority on the chemist Lavoisier, a biography of whom he published in 1964.9Lavoisier (Paris: Êditions Seghers, 1964). For Scheler’s other accomplishments see Antoine Corot, ed., Scheler (Lucien)…(Brussels: Bibliotheca Wittockiana, 1987), a fine annotated catalogue of a special exhibition documenting Scheler’s literary and bookselling career. From Scheler I was grateful to obtain the first edition of Nicolai Ivanovitch Lobachevskii’s treatise on non-Euclidean geometry (no. 1379). Published in the very obscure journal of the Imperial University of Kazan in five different issues over the years 1829-1830, very few sets have survived. When I purchased this in 1968 it was reputedly the only set outside of Russia. The copy used in the Grolier Club exhibition in 1958 had been lent by a Russian library, and the organizers of the original Printing and the Mind of Man exhibition had included only the German translation because they were unable to borrow a copy of the original printing. Another exceptional volume from Scheler was the collection of Baron Larrey’s personal copies of his papers collected by his son Hippolyte (no. 1278). A third was the presentation copy of Laennec’s De l’auscultation médiate (no. 1254), specially bound and inscribed by Laennec to his cousin Mériadec, the eventual editor of the third edition.

Georges Heilbrun favored exceptional copies of illustrated books. The most outstanding volume he let me have was the copy of Ramelli’s Le diverse et artificose machine (no. 1777), bound for Nicolas Claude Fabri de Peiresc, the scholar and patron of science, in full crimson morocco with Peiresc’s cipher stamped on the covers. Among the other works I purchased from Heilbrun were a beautiful copy of the Como Vitruvius (no. 2158) in contemporary blind-stamped black morocco, and a fine set of Buffon’s Histoire naturelle (no. 369). Heilbrun was the author of a significant bibliography of Buffon.10“Essai de bibliographie,” in Buffon (Paris: Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 1952), pp. 225-237. It was always a pleasure to visit him in his ancient Parisian home which had once been the residence of the great French bookseller and bibliographer, Brunet. Late in life this tall handsome man suffered a serious automobile accident that caused him to lose the use of his legs. Nevertheless he managed to travel around Paris on a motorbike.

Acquisition of the Vesalius in 1963 sent me on a quest for comparable items to add to my library. I decided to concentrate on presentation copies and association copies of the scientific and medical classics. Because these volumes are so difficult to find I would often buy a regular copy of work when it became available and attempt to upgrade it if a more interesting copy came along, trading in or selling off the inferior copy. As I became a more experienced collector I became increasingly aware of the importance of condition, and you will find some volumes in this catalogue which are in a most remarkable state of preservation in their original bindings. However, I have always been even more interested in presentation copies or association copies than in just fine condition per se. My quest for remarkable copies continued until completion of this catalogue in 1991. Although I am proud to have added many other great and interesting volumes to this library I have never been able to find a more remarkable volume than the Vesalius.

My burgeoning enthusiasm in the early 1960s was rewarded with several exceptional additions to the library. Among these, as mentioned above, was Esquirol’s personal copy, annotated for an unpublished second edition, of his De maladies mentales (no. 724). Purchased from Warren Howell, this was the first of the small number of author’s copies that I was able to obtain. At the Andrade sale at Sotheby’s in 1965 I purchased, via Dawsons of Pall Mall, what is apparently the only known autograph presentation copy of the first edition of Hooke’s Micrographia (no. 1092). Hooke seems to have been especially stingy with presentation copies. A more recent publication purchased from Hugh K. Elliot was the set of Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s Principia mathematica (no. 1868), presented to the mathematical logician Phillip Jourdain and containing Jourdain’s extensive annotations.

After Weil’s death in 1965 I was contacted by Arthur Lauria, an Italian bookseller resident in Paris. He informed me that he was the source for several books that Weil had sold me and volunteered to send me direct offers. During the next few years he was the source of first editions of Berengario da Carpi’s Tractatus de fractura calve sive cranei (no. 186) and Isagoge brevis (no. 188). More interesting to me was Vesalius’s edition of Guenther von Andernach’s Institutionum anatomicarum (no. 2135). When I purchased this from Lauria it was believed that the numerous annotations in this volume were corrections for a revised second edition in the handwriting of Vesalius himself. Even though the distinguished editors of this catalogue have been unable to confirm this assumption I remain satisfied that this was Vesalius’s personal copy. Certainly the handwriting resembles the few extant examples of Vesalius’s autograph.

During the years I have had excellent relations with other outstanding booksellers. Richard Gurney of London provided me with more material than any other dealer. He recognized my appreciation of special copies and was the source of several, including Sir James Young Simpson’s personal copy of his treatise on Anaesthesia (no. 1946). Another extraordinary volume from Richard Gurney was the copy of the first edition of Howard’s The State of the Prisons in England and Wales (no. 1108), bound for presentation with Howard’s inscription tooled into the spine. My copy of the first Japanese book on Western medicine, Kaitai shinsho (no. 1196) also came from Richard Gurney as did the first Western book on acupuncture, Willem Ten Rhijne’s Dissertatio de arthritide (no. 2062).

Several of my most important items of Americana came from Jo and Ralph Grimes of the Old Hickory Bookshop in Brinklow, Maryland, who specialized in early American medicine. Among these are Cotton Mather’s A Vindication of the Ministers of Boston (no. 1456), and Thomas Cadwalader’s An Essay on the West India Dry-Gripes (no. 385). This has the joint distinction of being both one of the earliest significant contributions to medical science by an American physician, and a product of Benjamin Franklin’s Philadelphia press. As far as we know it is the only copy remaining in private hands. From Jo Grimes I also purchased the presentation copy of John Morgan’s thesis, Pypoiesis (no. 1548) inscribed by Morgan, the founder of America’s first medical school, to the President of the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). The copy was later owned by the Philadelphia neurologist and novelist, S. Weir Mitchell. My presentation copy of William Beaumont’s Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice (no. 152), in its original presentation binding and with an autograph letter from Beaumont, also came from Old Hickory.

Henry Schuman, the leading American specialist in rare medical books in his day, died in the early 1960s before I had the opportunity to purchase much from him. Nevertheless he was responsible for a few of the outstanding rarities in my library, including Vesalius’s Epistola, docens venam axillarem dextri cubiti (no. 2136), the Ratdolt Euclid of 1482 (no. 729) and Georg Bartisch’s Augendienst (no. 125). Henry had the reputation for outrageous prices, but he had a wonderful sense of humor, and loved to bargain. He was also an enthusiastic amateur violinist and promised to visit me in San Francisco on the condition that I would arrange a quartet for him. Unfortunately, he died en route. From a catalogue published by his widow, Ida, who continued the business for some years, I purchased my 1495 edition of Ketham (no. 1211).

Emil Offenbacher, who recently died, was the last of the generation of antiquarian scholar-booksellers from whom I acquired most of my library. Many of these, including Otto Ranschburg, H. P. Kraus, E. Weil, and even Hugh K. Elliot, as well as Offenbacher, had been refugees from the Holocaust. In later years Offenbacher sent out one annual catalogue, from which I made many purchases. One of the best of these was the first edition of Ruini’s Dell’anatomia et dell’infirmita del cavallo (no. 1858). For a few years one of Offenbacher’s children lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, and the one time he visited me he brought with him the marvelous copy of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier’s Traité elémentaire de chimie (no. 1295), profusely annotated by the botanist Michel Adanson. With this came the autograph manuscript diary of Jean Êtienne Guettard (no. 953) recording his tour with Lavoisier in preparation for the geological atlas of France. Both of these treasures had previously been in the library of Denis Duveen, whose famous library on alchemy and chemistry was largely built by Offenbacher. My favorite later purchase from Emil was the presentation copy of the very rare offprint of James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth (no. 1130).

One of the few of my early sources still living is François Chamonal of Paris. I think immediately of five important items that came from him. First I think of the pocket Vesalius (no. 2138) in the Duodo binding. Then there is the special prepublication copy of Lavoisier and Guettard’s Atlas minéralogique de France (no. 1287) specially bound for the patron of the work, Henri Bertin, and Lamarck’s personal copy of his Système des animaux sans vertèbres (no. 1261). I was thrilled to have Jean-Martin Charcot’s personal copy of Parkinson’s An Essay on the Shaking Palsy (no. 1642), as it was Charcot who coined the eponym “Parkinsonism.” From François I also obtained another great rarity of nineteenth-century English science, a copy of Robert Brown’s privately printed Brief Account of Microscopical Observations (no. 353), which Brown had presented to the French botanist R. J. H. Dutrochet.

For several years I had an excellent relationship with Dawsons of Pall Mall. Beginning in the fifties they began to dominate the London scene in science and medicine, especially in the auctions. I was purchasing many books from their catalogues, and when I decided to broaden the scope of my collection Weil encouraged me to place my auction bids with them. In the process I became acquainted with Herbert Marley and his assistant and eventual successor, John Boyle. My biggest auction day was at the Andrade sale when Dawsons purchased for me Robert Boyle’s Sceptical Chymist (no. 299), the presentation copy of Hooke’s Micrographia previously mentioned, Robert Anderson’s The Making of Rockets (no. 54) and a few lesser items. All of these books exceeded the estimates Dawsons had proposed but they bought them anyhow and, as was their custom, offered them to me at their cost plus a ten percent commission. This was a very satisfactory arrangement for me.

All went well until at one sale I gave them my bid for a copy of Charles Bell’s Idea of a New Anatomy of the Brain (1811)—a work of the greatest rarity, since it was printed in an edition of only 100 copies. When the auction was over I was advised that I did not get the book. Later I discovered that in fact Dawsons had been the successful bidder and, as I recall, the price did not exceed by much the bid that they had originally suggested for me. When I tactfully asked for an explanation I was told by John Boyle that Marley had accepted a second bid and had given my bid to Boyle to execute. I was the victim of a private auction between the two. Boyle made it clear to me that he was also unhappy with the situation, but being a subordinate, had no recourse but to go along. He and I remain good friends, but after more than twenty years I am still indignant at what I consider to have been unethical conduct by Dawsons in this instance. I believe that a firm should only accept one bid on one book at one sale. This incident did temporarily dampen my enthusiasm for business with a firm to which I owe many great books. However I resumed actively purchasing from Dawsons as soon as John Boyle succeeded Marley as director. Over the years some of the more notable books I purchased from Dawsons were Theophrastus’s De historia et causis plantarum (no. 2066), Magnus Hundt’s Antropologium... (no. 1115), Christiaan Huygens’s Traité de la lumière (no. 1139), Antoine Jussieu’s Genera plantarum (no. 1194), Edmond Halley’s Astronomicae cometicae synopsis (no. 978), Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises (no. 1561), and Santorio Santorio’s Ars Sanctorii (no. 1890).

By the time I heard of the Viennese bookseller Herbert Reichner he had moved from New York to the small town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, taking with him his large inventory of European books on the widest variety of subjects. He issued catalogues replete with scholarship, but was better at finding and describing books than at selling them. This may explain why I was able to purchase from some of his old catalogues several remarkable rarities, including Janos Bolyai’s work on non-Euclidean geometry (no. 259), and Semmelweis’s Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis der Kindbettfiebers (no. 1926).

Another American dealer who was a pleasure to visit was Otto Ranschburg of Lathrop C. Harper in New York. Otto was another Viennese expatriate who functioned as this American firm’s expert on scientific and medical books. Otto was a pleasant and soft-spoken gentleman with a twinkle in his eye, and only about five feet tall. It was from him that I obtained, among other things, three outstanding mathematical rarities: Girolamo Cardano’s Ars magna (no. 400); Pierre de Fermat’s Varia opera mathematica (no. 778), and the editio princeps in Greek of Euclid’s Elements, inscribed by the editor Simon Grynaeus to the Strassburg physician Walter Ryff (no. 730). For years Otto had spoken of a European monastery that possessed two copies of the first edition of Avicenna’s Canon medicinae (1473) and implied that he hoped to persuade them to part with one copy. So it was my regular custom to ask him about this book whenever we spoke. Regrettably, he never bought that elusive rarity, and to this day I possess only a single leaf from the work, which I obtained from Maggs about thirty-five years ago. We did not deem this single leaf worthy of cataloguing.

The co-author of this catalogue, my son Jeremy, has become widely known as a specialist dealer in rare books and manuscripts on science and medicine. It has been one of the great pleasures of my life to have him as a pupil, companion, and occasional mentor in my bibliophilic adventures. He began to work at John Howell—Books in 1964 and quickly rose from packing room assistant to salesman. He continued to work with Warren through his undergraduate years at the University of California at Berkeley until 1969, when he left to begin his own business. During 1969-1970, when he was planning to open his own office, he prepared a preliminary card catalogue of my library. With his Catalogue One in 1971 he made his mark as a specialist and his reputation has grown each year. In the book world I am proud to be introduced as his father.

During the first few years of Jeremy’s business I hesitated to purchase his better books for fear that it would interfere with the development of his clientele. When it was clear that he was firmly established I became a progressively more significant customer. During the last decade he has provided the majority of my most important acquisitions. This is not only true because he knows my desiderata very well but also because so few of my former providers are alive. Also by being on the scene I am apt to have the same favorable advantage I formerly enjoyed with Warren Howell. Among the last works that Jeremy obtained for me was the group of three first editions of Freud’s early writings from the library of Freud’s closest friend and confidant at the time, Wilhelm Fliess (nos. F15, F26 and F33). The numerous books in the library supplied by Jeremy may be identified in the provenance index.

Besides the various collectors and booksellers already mentioned, I was also influenced by the catalogues of three notable collections, copies of which I acquired early in the 1950s: Bibliotheca Osleriana, The Harvey Cushing Collection of Books and Manuscripts, and the Bibliotheca Walleriana. Of these the Bibliotheca Osleriana impressed me most because it revealed to me something of Osler, the collector, both in its unusual arrangement of Bibliotheca Prima and Secunda, etc., and in his occasional comments about his books reproduced by the editors in the catalogue annotations. Certainly the Bibliotheca Osleriana was one of the inspirations for this catalogue. I have often recalled the pertinent reference Osler made to John Ferguson’s Bibliotheca Chemica (1906) in his address to the Bibliographical Society (1916): “It is the most useful special bibliography in my library and scarcely a day passes that I do not refer to its pages. The merit that appeals to me is the combination of biography and bibliography.” It is to be regretted that Osler was unable to complete the task of writing annotations for many of the books in his own library. The editors of his posthumous catalogue were apparently eager to preserve his notations but added virtually nothing of their own, which accounts for both the charm and the limitations of the catalogue. In many respects Osler, who valued first editions, condition, and provenance, was for me a model bibliophile even before I encountered his influence via Herbert Evans.

In 1934 Evans published a little catalogue entitled Exhibition of First Editions of Epochal Achievements in the History of Science, which was the precursor of Bern Dibner’s Heralds of Science (1955; rev. ed. 1980) and Harrison Horblit’s One Hundred Books Famous in Science (1964). As the references throughout this catalogue indicate, lists of this type were very influential on my collecting. So were numerous histories of science and medicine and biographies of figures who interested me, and the well-known exhibition of books and other printed materials entitled “Printing and the mind of man,” held at the British Museum and Earl’s Court, London, in July 1963. I was, of course, also very influenced in my selection of books in medicine and the biological sciences by Morton’s A Medical Bibliography (Garrison-Morton), from its first edition of 1943 through the fourth edition of 1983.11Except for association copies we decided not to include any of my regular reference books in the main body of the catalogue. The most useful reference works and bibliographies on all subjects concerned with this catalogue are cited throughout the catalogue and in the list of references at the end. I am proud that my son, Jeremy, has assumed editorship of this comprehensive work, beginning with its fifth edition to be published in 1991.

I began this library by making a Freud collection and eventually found the first edition of almost every book and paper he wrote. However, most of the books were in average condition. To obtain first editions of Freud’s many journal articles I initially collected sets of the various periodicals in which they originally appeared. However, as my connoisseurship improved I decided to limit myself to the rarest and most unusual items. My Freud collection, as it now stands, contains several of Freud’s personal copies and about thirty presentation copies inscribed by him. It is sufficiently extensive that we separated it from the rest of the catalogue and published it as an appendix. Stanford University Libraries also published a separate exhibition catalogue of my Freud collection (1991). The annotations in that work were abridged from our more extensive desciptions published here, and were arranged thematically rather than chronologically as in this catalogue.

As a second appendix we have described my extensive collection of the works of Franz Anton Mesmer and on mesmerism. I became interested in Mesmer for his place in the histories of hypnosis and psychotherapy. Today Mesmer and the enormously wide interest stimulated by his work in France before the revolution is also studied by social historians. In reviewing the Mesmer collection I note that it contains no presentation copies by Mesmer. I cannot recall ever seeing a work inscribed by Mesmer either in libraries or on the market. I do have two Mesmer letters in the collection, one of which has very significant content (see no. M35). Other authors whom I at one time or other also started to collect in depth were Louis Pasteur and Claude Bernard. However, I eventually abandoned these objectives, deciding to limit myself to what I thought were their most significant writings, preferably in presentation copies.

It may be appropriate here to comment on the issue of offprint versus journal number which Harrison Horblit raised in the catalogue of the Grolier Club exhibition. Harrison believed that the journal was the real first edition since this was the form in which the author first reached his public. While this is certainly true, the offprint (sometimes also called “reprint”, a name I regard as inappropriate since it implies a later printing) is certainly the more interesting version of the paper to collect since it is so much rarer and more personal. Usually issued in fifty copies or less, the offprint is the version of the work that the author personally sent to friends and colleagues, and of course, this is the version that the author was apt to inscribe for presentation. An example of the distinction between the journal volume and the offprint that comes to mind is the first edition of Oliver Wendell Holmes’s paper on the Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever (no. 1088). Years ago I obtained at auction the first and only volume of the New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery, itself a great rarity. Nevertheless I remembered Osler’s words from 1902, “If you can find the original pamphlet on the Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever, a reprint from the New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery, 1843, have it bound in crushed levant—’tis worthy of it.” When Jeremy acquired a copy of this excessively rare offprint I purchased it at once and sold the journal volume. However I did not follow Osler’s instructions literally with respect to rebinding the pamphlet, retaining it in its fine condition in the original printed wrappers, and having it enclosed in a protective case. Standards for preserving works in their original condition have advanced since Osler’s time.

For several years it has been my ambition to obtain the offprint of journal publications; however, many offprints are impossibly difficult to obtain and we have catalogued the journal volume when I could not obtain the offprint. In some instances, such as Einstein’s “Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper,” we have catalogued both the journal volume and the offprint (nos. 691 and 691a). For the “Darwin-Wallace papers” (nos. 591 and 592), I have the two versions of the journal issue but can recall seeing the offprint on the market only once in forty years; unfortunately, I was too late to obtain it.

Some of the most unusual and valuable books in my library are the special copies in fine bindings. My interest in bindings developed gradually because it is so difficult to find books with major scientific or medical content in significant bindings. Whenever possible I attempted to acquire examples available. We have taken care to illustrate nearly all of the unusual bindings in the library, in color where appropriate. The bindings can be identified most easily from the illustrations list. When the binder’s name is known it is included in the index of artists and binders. The smallest notable bindings in the collection are on the set of the pocket reprint of Vesalius’s Fabrica, bound for Pietro Duodo (no. 2138). By far the largest is the design binding on the very heavy copy of the Bremer Press Vesalius (no. 2145), which Jeremy commissioned from Michael Wilcox for my seventieth birthday. The protective box that Wilcox constructed to protect this large folio weighs more than the book itself.

Students of this catalogue will notice that I have collected very few manuscripts. As a rule I never set out to collect manuscripts, and the few that have been catalogued relate to books I possess, such as the Guettard diary (no. 953), the Mesmer letters (nos. M17 and M35), Lamarck’s review and license of Jussieu’s Genera plantarum (no. 1259), and Freud’s letters to Max Marcuse (no. F66). Like other collectors who purchase books chiefly for their content, I generally believed that most of the manuscripts offered did not contain significant enough content, and in the few cases when the content genuinely interested me I was already sufficiently committed to book purchases that I did not want to divert the funds to the manuscripts. The large number of autograph presentation copies in the collection represent my compromise between collecting books and manuscripts. In a few cases the presentation inscriptions are quite lengthy; see, for example, Cushing’s The Pituitary Body and its Disorders (no. 549).

While this catalogue records the many fine books I acquired, I still regret some of the books I did not purchase. In forty years of collecting I occasionally passed up a great book more than once. As an example of the sort of mistake a collector can make we may review the extraordinary sales history of the Horblit/Rheticus copy of Copernicus. As far as my son Jeremy and I have been able to determine, the copy was found about 1960 by the London bookseller William Fletcher, and sold by him to Philip and Lionel Robinson. The Robinsons sold it to Horblit for about $10,000 circa 1962, just before Weil tried to acquire it for me. In about 1970 Lew David Feldman, who knew of my interest in the copy, suggested that it could be bought privately for $50,000; however, having missed the copy at $12,000, I could not justify the purchase to myself at a substantially higher price. This was a decision I would later much regret, as in the first of Horblit’s auctions at Sothebys in 1974 the copy sold for £44,000 (then about $100,000). It was purchased for stock by Lew Feldman, who offered it for $150,000.12Feldman, L. D. Fortieth Anniversary Catalogue. New York: House of El Dieff, 1975 (item 3). For many years this was a record price for a science book, and the copy remained in Feldman’s inventory for two years before he eventually sold it to Haven O’More (The Garden, Ltd.). In the auction of the library of The Garden, Ltd. at Sotheby’s, New York, 1989 the copy sold for $430,000 plus premium.

For some reason my experience with the first edition of Copernicus was never quite satisfactory. In 1981 I purchased a fine copy, without provenance, from Warren Howell (no. 516). A few years later Howell discovered, to his considerable embarrassment, that it had been stolen from the John Crerar Library (now at the University of Chicago), and requested its return. The unfavorable publicity that Warren received late in life because of his unwitting sale of this and other books stolen from the John Crerar Library was a blemish on an otherwise proud and successful career. Warren died before the case could be adjudicated (it was finally settled out of court), and eventually I received financial compensation from his estate. Although the Copernicus is no longer in my library we decided to include its description as a sort of cautionary tale.

Apart from the numerous advantages and pleasures of preparing the catalogue of this library, I also feel that there were a few disadvantages. One is the unsuspected discovery of a defect in a copy. This happened with my copy of Durer’s Menschlicher Proportion (no. 666), which turned out, upon Diana Hook’s collation, to lack a complete signature of six leaves. The defect apparently went unnoticed by Warren Howell when he sold me the copy, and also by Louis H. Silver, its previous owner. I have already mentioned my disagreement with the authors of the catalogue concerning the attribution of the manuscript notes in what I still think is Vesalius’s copy of Guenther von Andernach’s Institutionum anatomicae (no. 2135).

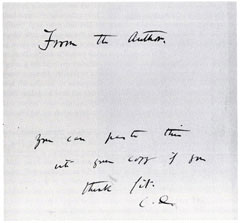

Another problem, but one for which I am at least partially to blame, is Boerhaave’s presentation copy of his edition of the collected works of Vesalius (no. 2143). The elegant inscription in this volume was removed from an inferior and incomplete rebound copy of the same work, which Jeremy felt did not meet my standards. In retrospect I feel it would have been better to have kept the inscription in its original volume. Conversely there is my copy of the first edition of On the Origin of Species (no. 593). It is a presentation copy inscribed, as all known presentation copies of this work, by the publisher’s clerk. My copy also has laid in a sheet inscribed in Darwin’s hand: “From the author/You can paste this/into your copy if you/think fit. C.D.” Admittedly I was always tempted to paste this into mine, but whenever the urge became strong Jeremy would discourage me.

The catalogue you have before you would not have been possible without Jeremy’s committment and effort. He originally volunteered to undertake it in repayment for some financial assistance I provided when he opened his business twenty-one years ago. By 1984 he felt sufficiently established to begin the project, and was able to hire Diana Hook, a rare book cataloguer with excellent bibliographical training, whose professional skills made her a superb collaborator in this work.

This narrative of my education as a bibliophile has been intertwined with the names of those who inspired me, such as Sigmund Freud, Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing, and Erik Waller, and of those whom I wished to emulate, including Herbert M. Evans, Harrison Horblit, and Robert B. Honeyman, and of the rare book dealers who provided the books that are the substance of this library. We hope that the catalogue will be seen as a fitting tribute to those booksellers, and that it will serve as a guide for those who follow in my pleasurable quest for the great books in science and medicine.

« back to all Articles

back to top